I have been asked to explain further the ‘deep or wide’ anecdote about Anglo Catholics.

I really did not mean to offend, and sincerely apologize if the comment caused offense.

What I meant was this: that the external differences between Anglo Catholicism and Catholicism present a rather narrow gap. Indeed, the theological and liturgical differences also present a fairly narrow gap (at least between Catholics and what we might call ‘historic’ or orthodox Anglo Catholics)

However, the chasm between us is deep. I say it is ‘deep’ because it is deep down and hidden. It is written into the genetic code of Anglicanism and Catholicism. Because it is so deep down I find it hard to articulate, and if I do recognize this it is not meant to be a criticism of Anglicanism per se.

I am observing this subjectively, and yet I think dispassionately. The deep down differences have to do with how Catholics understand themselves, and Christ and history and the Church and (it must be said) their ethnicity. This is very different from the way Anglicans (and this includes Anglo Catholics as a subset) understand themselves and Christ and history and the Church and their ethnicity.

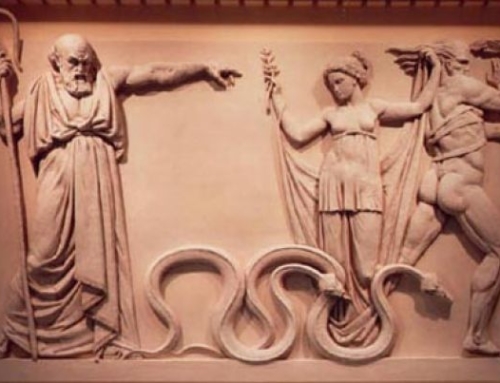

As a convert I am still gazing deeply into this crevasse and trying to understand. It is all tied up with (among other things) Irishness and Italian-ness and Spanish-ness and Hispanic-ness. It is linked with the absurdity and radical nature of Catholic sanctity and saints. Deep down it is about the depth and strangeness of Catholic spirituality and sacramentality. It has to do with antiquity and universality and infallibility and being part of a supernaturally subversive world order within the realm of history. Somehow Catholicism is a product of the ancient world of paganism and Judaism and the Middle East and Rome whereas Anglicanism in all its forms, (and Anglo Catholicism, for all it’s virtues, is simply another expression of Anglicanism) is a product of Protestantism and Rationalism and Northern Europe and the sixteenth century.

It has to do with depths I can’t explain, but which I know are there operating within myself and within the cosmos–depths that I never sensed in Anglicanism, depths which my experience in Anglicanism prepared me for, but which I did not find there except in part.

Again, I do not say this with any sense of animosity or blame. I am simply reflecting my own experience and say that it feels like I have moved from the entrance hall into a vast and ancient country mansion, from a tributary into a mighty river that is bearing me to the endless sea.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Sorry …. my comment self-deleted above because of hastily-typed spelling mistakes! I’ll try again:As a convert from Anglicanism (though never a high church type, really. More an Anglican with a catholic spirituality) myself I can thoroughly concur. But, yes, it is hard to put it into words. The culture is so different and … Catholic! In Anglicanism it just isn’t there – even when there is a real effort to argue and prove that it is. It’s a sort of intellectual construct for Anglicans. For Catholics it’s a life-giving reality. That’s probably as clear as mud!!

I take your point, Father, and probably, as a generalization, your concept of a Catholic ethos as opposed to a Protestant ethos has a lot of merit.However, it makes very little difference if this is so, if it’s not true “on the ground.” So, the Roman Catholic parishes in much of this country are, in my experience, not particularly imbued with this Catholic ethos. They are largely–as a friend likes to say–mainstream American Protestants with (in better cases) the Rosary and Exposition. So, in places where one of the few bastions of Anglo-Catholicism remains, the contrast between that community and the local Roman Catholic parishes illustrates your point nicely; albeit in the reverse!Returning to your anecdote, for certain Anglo-Catholics at least, I submit that it is not a question of either a deep or wide separation, theologically or otherwise, but rather only a desperate desire to cling to an authentically catholic culture which they have been unable to find elsewhere.But this doesn’t really speak against your broader point, I suppose, only to the fact that it doesn’t apply universally. Though I think that apologists, and especially convert apologists, would do well to take this into consideration.

“Not wide. Deep.” I think that’s a very good way of putting it. It’s hard to articulate the depth of the divide without seeming to accuse Anglo-Catholics of self-delusion, and I certainly don’t intend to do that, but it’s definitely there. (I say this, admittedly, with little experience of Anglicanism beyond formerly frequenting Evensong in a spirit of ecumenism.)

Oh, and helping out as a volunteer in a C of E primary school.

I was just trying to explain this very thing to a friend of mine about the difference between Catholics and Evangelicals. They’re very similar in many ways (sin, salvation…) but where they differ (papal authority, the Eucharist, Mary…) the differences are very, very deep.Please thank your wife for me.

The chasm between the Catholic Church and any sort of protestantism whatsoever is deep and narrow. A sparrow is not a finch, but they are both birds. What is peculiar is a finch that puts on vestments and calls itself a sparrow. A courteous sparrow may speak to that finch with friendliness and “sensitivity”, but it will draw the line at mating.

Beautiful imagery of the tributary and river…moves my soul….

Food for thought, Father. Growing up in Ireland at a time when Catholics numbered over 90% of the population and most were still practicing, we had a rather caustic view of our ‘separated brethren’. Regardless of whether they were Church of Ireland, Presbyterian or Methodist, all were lumped under the heading of ‘Protestant’, with little distinction of provenance – whether it was Martin Luther, Calvin, Zwingli or Henry VIII.The gap was even wider if you considered – as we did growing up – that they were ‘all English’, if not by birth, at least (we assumed) by inclination. No matter that they could trace their roots back through hundreds of years of Irish ancestry – and many of their ancestors had died for ‘The Cause’ – we tended to look upon them as part of the ‘Invading English’ who had wrested the land from us. So, there was a ‘political’ as well as a religious element to the divide. Added to that was the fact that most non-Catholic Irish at the time (in the Republic, at least) tended to be well-to-do, there was a social divide. We didn’t know many poor non-Catholics!Being pre-Vatican II, there was little talk of or inclination towards ‘Ecumenism’. On the contrary, they were seen as a danger to the Faith and, if not to be completely avoided, they were to be looked upon guardedly. The hierarchy and the local Parish Priest inveighed against ‘mixed marriages’ which would be seen not just as a danger to the Faith, but as a betrayal. While we might have prayed in general for ‘the conversion of England’ we probably didn’t think of praying for the conversion of Mary Smith who lived on the next street. I suspect we didn’t think much about doctrinal differences back then either. It was pretty much black and white. They didn’t accept the Pope. We did. We could trace our origin back to Christ Himself. They could only go back a few centuries. We’re not going to change. They’re going to have to. End of story.Looking back on it now I can see there was a lot of smugness, arrogance and pride in our attitude and little of the humility that should have come from those “to whom much had been given and from whom much would be expected”. While we could, and did, send thousands of priests to foreign lands to preach the Gospel, we were lacking in living the Gospel among those closer to home.“Who is my neighbor?” Our Lord was asked. Fifty years ago I doubt that we would have given the right answer. I hope we have learned since then…Mea culpa.

Paul Goings,I identify thoroughly with your comments about the lack of Catholic ethos in most Roman Catholic parishes today. However, it seems to me that the very idea of clinging to an “authentic catholic culture found elsewhere” is a Protestant one. Since my conversion from Anglicanism, I have found that often we have to give up EVERYTHING we desire to follow our ONE desire, which is Jesus Christ in the Holy Eucharist. I place my trust in him, and in his promise to guide and protect his church. The rest I offer as penance, while doing whatever I can to teach the faith and improve the situation. It’s a hard leap though – I feel for you.

This is interesting, Father.Of course you’re right about a lot of things. But given your self-described subjectivity here, why make such generalizations? They’re probably, generally, right, but never the whole picture, as Paul Goings suggests above. My own experience suggests nothing about Anglicanism in general, but rather that my generation of Anglo-Catholics do not see themselves in the way that you describe… if the latest articulations of Anglo-Catholicism are products of protestantism and rationalism then so are the latest articulations of Catholicism. We cannot be defined solely by such things. So as far as I’m concerned you’ve got the generalizations wrong. There may be a deep and narrow divide — but that is a much simpler divide, the deep division of sacramental communion. In terms of “how Catholics understand themselves, and Christ and history and the Church and their ethnicity” I’d take your average Anglo-Catholic as a much likelier candidate for Catholic Christianity than your average Roman Catholic in America.