This article was first published in St Austin Review

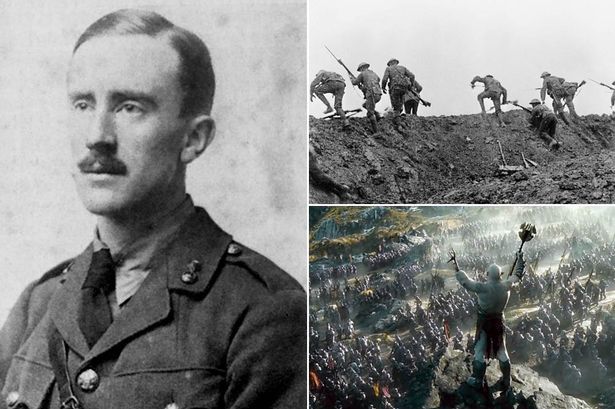

Out of the nightmare of the Somme came a sickly scholar who would gather up the tragedy of the trenches and turn it into the unexpected literary triumph of the century. Despite the derision of the academics, J.R.R.Tolkien’s masterpiece continues to be hailed as the most popular book of the twentieth century and Tolkien himself as the author of the century.

In an important study, John Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War chronicles the roots of Tolkien’s work in his experiences in the first World War. In a review of Garth’s book for the journal Religion and Literature, Terrence Neal Brown sees the genesis of Tolkien’s literary, religious and moral vision in the conversations among a group of Tolkien’s school friends who called themselves “The Tea Club Barrovian Society”. Along with Tolkien, Christopher Wiseman, J.B.Smith and Rob Gilson formed a literary club at King Edward’s School in Birmingham not unlike the Inklings, who met to drink tea and discuss literature, religion and life.

The idealistic Smith “declared that through art the four would have to leave the world better than they found it.” Their calling was to re-establish sanity, cleanliness and the love of real and true beauty in everyone’s breast.” All four of the bright eyed young men would be caught up in the brutal reality of the war. Smith and Gilson perished on the Somme, Wiseman survived Jutland and Tolkien, also serving on the Somme, caught trench fever and was sent home to recover.

It is from these first hand experiences of war that Tolkien was to find the ground and content for a fantasy that was empowered by vivid realism. Writing in his essay on fairy stories, Tolkien records, “A real taste for fairy stories was wakened by philology on the threshold of manhood, and quickened to full life by war.”

C.S.Lewis, who was himself wounded in the battle of the Somme, recognized the landscape of war in Tolkien’s masterpiece. Reviewing The Two Towers and The Return of the King for Time and Tide in 1955, Lewis writes, “This war has the very quality of the war my generation knew. It is all here: the endless, unintelligible movement, the sinister quiet of the front when ‘everything is now ready.’ the flying civilians, the lively vivid friendships, the background of something like despair and the merry foreground…that is why we can say of his war scenes (quoting Gimli the dwarf) ‘There is good rock here This country has tough bones.’ ”

The realism of the great battle which takes place in The Lord of the Rings springs from Tolkien’s war experiences, but so does the key friendship of the story. The true hero of the tale is Samwise Gamgee, who Tolkien acknowledged in a private letter, was based on the batmen in the war–the working class servants of the officers. With typical modesty Tolkien writes, “My Sam Gamgee is indeed a reflexion of the English soldier, of the privates and batmen I knew in the 1914 war, and recognized as so far superior to myself.”

Unlike so many others of his generation, Tolkien did not emerge from the war despondent and despairing. Instead, the war became the crucible out of which he forges a masterpiece of hope and heroism, providence and protection, confidence and faith. Tolkien projects from his personal experiences the universal lessons that life is itself a great battle to be fought and a heroic quest to be undertaken.

Eschewing any idea that the story was an allegory about the atomic bomb and Russia, Tolkien creates a mythic world where universals become particular, and because they become particular in Middle Earth they are also alive on this earth. In his review of the book, C.S.Lewis writes, “the text itself teaches us that Sauron is eternal; the war of the Ring is only one of a thousand wars against him. Every time we shall be wise to fear his ultimate victory…If we insist on asking for the moral of the story, that is the moral: a recall from facile optimism and wailing pessimism alike, to that hard, yet not quite desperate, insight into Man’s unchanging predicament by which heroic ages have lived.”

Tolkien’s task of turning the terror of war into a magnificent myth was only possible through the perspective of his Catholic faith which taught him that life was a conflict, but that the beautiful, good and true would ultimately prevail. By translating the horrors of war to the great war of the ring, he reminds every generation of the eternal reality of evil, the need to engage in the fight for beauty, truth and goodness in order to “re-establish sanity, cleanliness and the love of real and true beauty in every breast.”

The schoolboy Tolkien understood his friend’s glimpse of glory. Sensing his destiny Tolkien replied to Smith that he believed he and his friends had been “granted some spark of fire” and that they were “destined to kindle a new light or re-kindle an old light in the world…that they were destined to testify to God and the truth in a more direct way even than laying down their lives in a great war.”

The Lord of the Rings re-kindles the light not by treating the great war romantically, but by treating it realistically. The paradox is that Tolkien treats the war realistically by re-casting it as a great myth. Lewis explains how myth makes ordinary things more real not less real, “The value of the myth is that it takes all the things we know and restores to them the rich significance which has been hidden by the ‘veil of familiarity’…by putting bread, gold, horse, apple or the very roads into a myth we do not retreat from reality. We rediscover it.”

Tolkien’s redemption of the great war through myth changes our perception of history because it changes our perception of ourselves. Tolkien is the greatest author of the twentieth century, because his work changes lives. As Lewis wrote prophetically at the end of his 1955 review, “We know at once that [this book] has done things to us. We are not quite the same men.” As we embark on the quest with the hero the great war still lives; like Tolkien and Lewis, we are part of it, and when faced with that reality, as Gandalf says, “ All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

REMEMBER: Until December 2 I am running my annual Donor Subscriber membership drive. If you appreciate this blog-website and like having most of the content available not only free of charge, but free of all advertising please consider supporting my work by being a Donor Subscriber. In addition to all the free content, Donor Subscribers have access to more material.

As part of my annual upgrade I have added a new level of Donor Subscriber. Full Donor Subscribers contribute $8.95 a month and enjoy a range of benefits. Podcast Donor Subscribers can enjoy just the archived podcasts and a few other benefits. This lower rate is just $4.95 a month. That’s less than $1.25 a week or just 18 cents a day.

There’s more! All new subscribers during the membership drive can request a free book.

Remember, your involvement helps make this content available to thousands of readers and listeners worldwide who can’t afford a subscription. Go here to learn what the benefits are and how you can become a Donor Subscriber. SUBSCRIBE HERE

Not long ago I found a facsimile of my grandfather Arthur’s draft card for World War I. He and my great uncle George were about the same age, born in 1892 and 1893 respectively. Uncle George was sent to France. Hearing their stories as a young boy when they would speak casually about “Gwine to France to fight Kaiser Bill” seemed like stuff of legend. It was difficult for me to imagine the world they described; a world war that consisted of as many mules and horses as tanks. A war in which global powers were still beholden to throne and altar. Perhaps if I had been a bit older I would have asked more probing questions. By the time I discovered Tolkien in High School both my grandfather and great uncle were passed. Reading of Tolkien and how he and his work were shaped by the war helps me feel connected to my grandfather and great uncle. The world we live in, a world of a divided middle east, a smaller Germany, no Prussia, a belief (or skepticism of modernity) it all descends from World War I. The Great War, to end all wars …