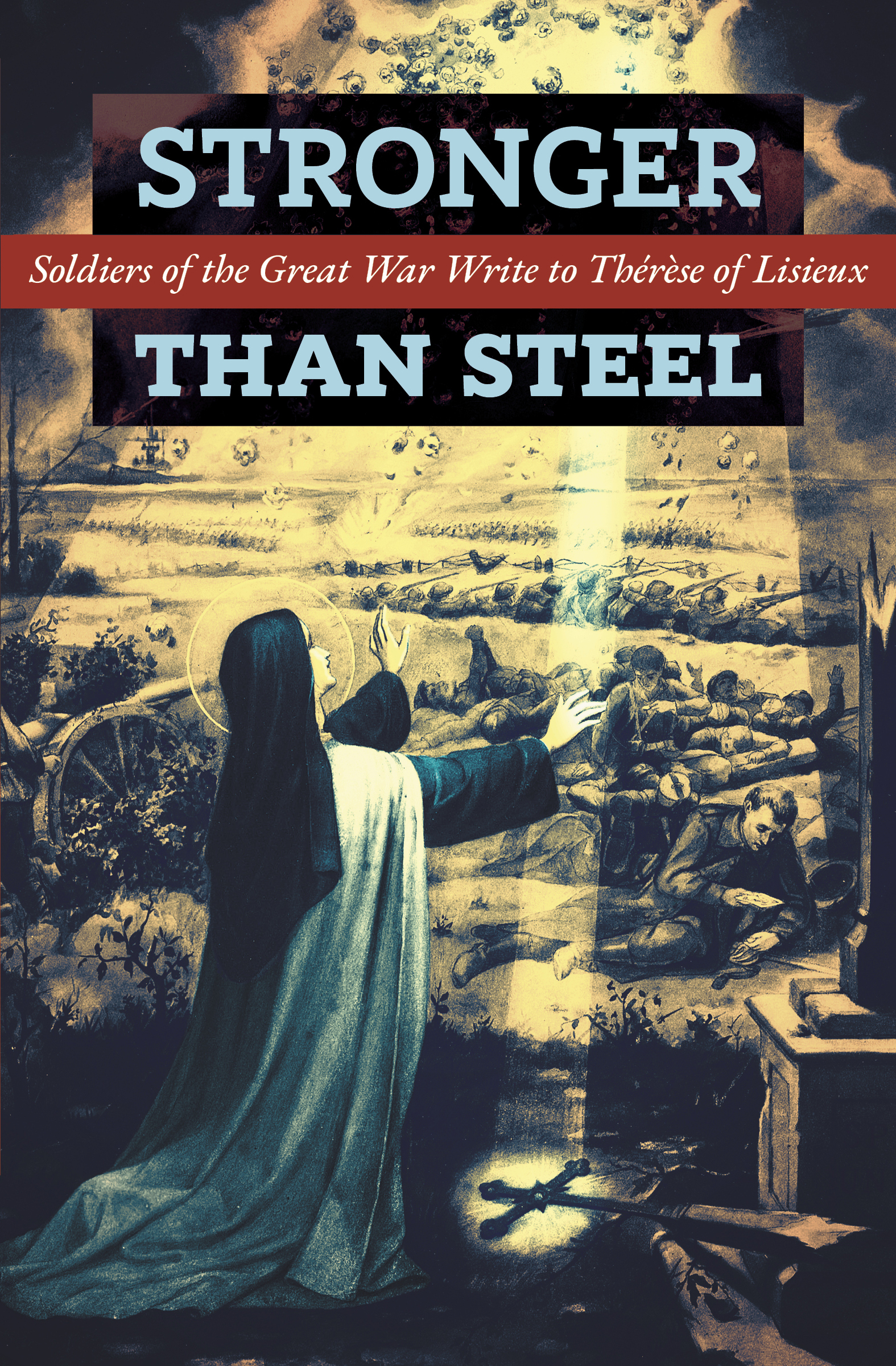

I have worked with the good folks at Angelico Press to bring to an English speaking audience a most remarkable book. Stronger Than Steel is a collection of letters from (mostly) French soldiers fighting in World War I. They were sent to the Mother Superior of the Carmelite convent in Lisieux and recount the marvels and miracles the men experienced through their devotion to St Therese.

I am sharing an excerpt with you here from one soldier’s experience in the Battle of the Marne. The first Battle of the Marne took place in September 1914, in the eponymous French “department.” It blocked the German advance into France, leading to a war of position on the Western front, a stalemate that was to last until early 1918.

Here is one of the letters…

On September 7, at the battle of the Marne,

Our Infantry Regiment was located halfway between Montceaux-lès-Provins and Esternay gathered behind a small birch wood; on the other side of the wood, in order to reach the village, we had to cross an open ground made of two large fields, a stalk field and an alfalfa one. It was no easy business, since these fields were being swept with enemy machine-gun fire and shells; a patrol of five men and an officer had just been mowed down there, with none of them getting back on his feet. The 1st Section of the 8th Company, of which I was part, followed by the other sections, came out of the wood first and deployed as skirmishers advancing in bounds, but the ground had been carefully scouted out by the enemy, which was spraying us copiously with its shells. The rumbling of the shells, the noise they made when they burst, mingled with the whistling of the bullets and the rat-a-tat of the machine guns were such that we literally had to yell to make ourselves heard. We had crossed only 60 meters, and a full third of our troop was already out of action. The lieutenant had fallen stone-dead at the first rush, the warrant officer and the sergeant major at the second one. Unable to move forward though backed by other companies, we were holding our ground, waiting for our artillery to arrive; blocked, lying flat on the ground, becoming one with the ground, as it were, we responded as best as we could to the shots of the enemy safely sheltered in front of the village and in its first houses.

It was certainly not more than fifteen minutes before we heard over our heads the response our 75th were sending to the enemy batteries. The man on my right side had just been killed instantly by a bullet shot right into his head, the man on my left had a leg broken by shrapnel and also a piece of shrapnel in his shoulder. Well, in such circumstances minutes feel like hours, and one’s mind works quickly. Never doubting it would soon be my turn, I silently renewed my act of contrition; this is when I remembered the little Sister Therese, of whom my mother had given me a relic that I carried with me. I began to invoke her, saying: “Little Sister Therese, I don’t know you, but Mother prays to you and likes you; if you get me out of this bind, I’ll go on a pilgrimage to Lisieux and will do all that I can to spread your name within my circle of friends and relatives.” I then resumed shooting, waiting for the shot that would hit me, and . . . it never came. A few moments later, backed by a new battery pulling down the houses where the Germans had taken refuge, we launched an attack on the village and took it, while the enemy was hastily leaving the place.

Since that day, I have experienced tough affairs many times; none of them, however, ever compared with what happened on September 7, because we had to fight on open ground. I most definitely owe my life to the protection of the little Sister, to whom I have kept praying ever since in all difficult times. No need to say that, having obtained a leave following an illness, I went to Lisieux to thank the little Sister and request her assistance for the future, and sent relics to all my comrades at the front. They were received with gratitude.

Go here to purchase the book.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.