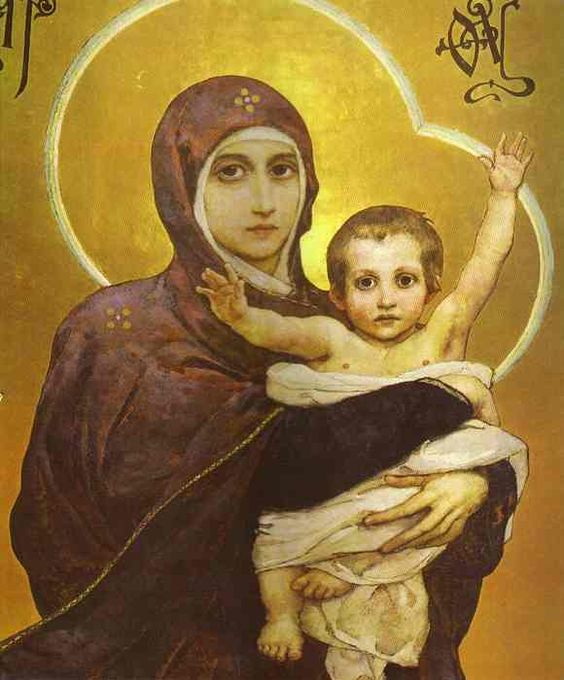

On her birthday I would like to explain why this is one of my favorite images of the Blessed Virgin Mary. First of all, I should explain where it comes from. It is by the nineteenth century Russia painter Victor Vasnetsov. One gigantic, full length ver sion of it can be seen in the apse of St Volodymyr Cathedral in Kiev.

sion of it can be seen in the apse of St Volodymyr Cathedral in Kiev.

The reason I am so taken with the image is because, while I like the classic icons of the Blessed Virgin and the sweet images of Raphael, this image communicates something more mysterious and marvelous about the Virgin. First of all, she actually looks like a Middle Eastern young woman–in fact she looks like she is only about fourteen years old. The Christ child and his mother both show the austere solemnity from the Russian tradition of iconography, but with a fresh naturalistic appeal.

The challenge for any Christian iconographer is to show Our Lord, the Blessed Virgin or the saints as real people, but extraordinary at the same time. If the image becomes too realistic/naturalistic we lose the sense of the spiritual–the fact that Our Lord was God Incarnate, the Blessed Virgin was “higher than the seraphim, more glorious than the cherubim”. The saints were ordinary people transformed by grace to become divinized–the ultimate perfection of the human children of God.

How does the painter or sculptor portray both their humanity and their divinity or graced perfection?

If he goes too far in the other direction–trying to portray their supernatural qualities the image can become over sentimentalized, weird or just plain spooky. This is why part of the iconographic tradition in both East and West portrayed the human figures with elongated figures and stylized, classical gestures–gestures of nobility, grace and great dignity. They were trying to show the majesty and beauty of the saints who had been transformed by grace.

This image by Vasnetsov is, to my mind, wonderfully successful in the ambition. The Blessed Virgin and the Christ child look natural and realistic as humans, but Vasnetsov has captured what must be for our eyes, an exotic quality. This girl is a girl like no other, and her Son is magnificent in the brooding power and pathos of his face. There is no hint of sentimentality or weirdness, but there is still the disturbing unrelenting gaze. Both the mother and child look into our hearts and through our hearts to the eternal questions.

I also like the image because Vasnetsov capture in Mary’s Semitic appearance the Jewish roots of our faith. By fusing the Eastern iconographic traditions with the naturalism and romanticism of the West he also captures the poignant division between the Eastern and Western churches and somehow offers this image of the Incarnation as a sign of unity between the past and present, the fusion of Jewish and Gentile and the traditions of East and West.

Finally, the double nimbus and the light glowing behind and between the two of them speaks in abstract terms of the shared light of their shared life. The Virgin and her Son are one in the unity of earth and heaven that is contracted through the mystery of the incarnation. He takes her flesh. She takes a measure of his divinity within her own body and the bridge between this soiled earth and sublime heaven is achieved as both a historic reality a present hope and a future destiny.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.