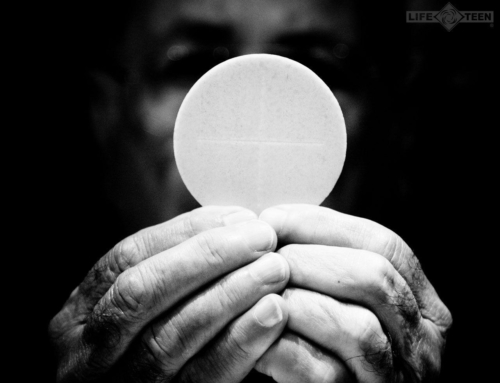

On this Feast of the Chair of Peter the photograph with this post is the cathedra or Bishop’s Throne in the Cathedral Church of St John Lateran–the cathedral of the Bishop of Rome and the seat of his authority as the Successor of Peter. This long article charts the early development of the papacy and critiques some typical misunderstandings about the early church.

The Trail of Blood

Some time ago an acquaintance from my days as a fundamentalist sent me an email. Kevin had become a Baptist pastor and was disappointed that I had been “deceived by the Catholic Church”. He wanted to know my reasons for becoming Catholic.

I get such emails from time to time, and rather than get involved in arguments about purgatory or candles or Mary worship or indulgences, I usually cut straight to the point and try to engage my correspondent with the question of authority in the Church.

Kevin told me that to follow the Pope was an ancient error, and when I asked where he got his authority he promised to send me a book called The Trail of Blood. This book, written by a Baptist pastor called J.M.Carroll explains that Baptists are not really Protestants because they never broke away from the Catholic Church. Instead they are part of an ancient line of “true and faithful Biblical Christians” dating right back through the Waldensians and Henricians to the Cathars, the Novatians, Montanists and eventually John the Baptist.” This view is called Baptist Successionism or Landmarkism and it is also taught by John T Christian in his book, The History of the Baptists.

Baptist Successionism is a theory more theological than historical. For the proponents, the fact that there is no historical proof for their theory simply shows how good the Catholic Church was at persecution and cover up. Baptist Successionism can never be disproved because all that is required for their succession to be transmitted was a small group of faithful people somewhere at sometime who kept the flame of the true faith alive. The authors of this fake history skim happily over the heretical beliefs of their supposed forefathers in the faith. It is sufficient that all these groups were opposed to, and persecuted by, the Catholics.

Most educated Evangelicals would snicker at such bogus scholarship and many more are totally ignorant of the works of J.M.Carroll and the arcane historical theories of Baptist Successionism. Nevertheless, the basic assumptions of Baptist Successionism provide the foundation for most current independent Baptist explanations of early Church history, and these assumptions are the foundation for the typical independent Baptist understanding of the Church. The assumptions about the early church are these: 1) Jesus Christ never intended such a thing as a monarchical papacy 2) The church of the New Testament age was de-centralized 2) the early church was essentially local and congregational in government. 3) The church became hierarchical after the conversion of Constantine in the fourth century and 4) the papacy was invented by Pope Leo the Great who reigned from 440 – 460.

Just the Facts

The basic assumptions the typical Evangelical has about the papacy are part of the wallpaper in the Evangelical world. Being brought up in an independent Bible Church, I was taught that our little fellowship of Christians meeting to study the Bible, pray and sing gospel songs was like the ‘early Christians’ meeting in their house churches. I had a mental picture of ‘Catholic Pope’ which I had pieced together from a whole range of biased sources. When I heard the word ‘pope’ I pictured a corpulent Italian with the juicy name “Borgia” who drank a lot of wine, was supposed to be celibate, but who not only had mistresses, but sons who he called ‘nephews’. This ‘pope’ had big banquets in one of his many palaces, was very rich, rode out to war when he felt like it and liked to tell Michelangelo how to paint. That this ‘pope’ was a later invention of the corrupt Catholic Church was simply part of the whole colorful story.

But of course, the idea that the florid Renaissance pope is typical of all popes is not a Catholic invention, but a Protestant one. Protestantism has been compelled to rewrite all history according to it’s own necessities. As French historian Augustin Thierry has written, “To live, Protestantism found itself forced to build up a history of its own.”

The five basic assumptions of non-Catholic Christians can be corrected by looking at the history of the early church. Did Jesus envision and plan a monarchical papacy? Was the early church de-centralized? Was the early church essentially local and congregational? Did the early church only become hierarchical after the emperor was converted? Did Leo the Great invent the papacy in the fifth century? To examine this we’ll have to put on one side the preconceptions and mental images of Borgia popes and get down to ‘just the facts ma’am.’

Did Jesus Plan a Monarchical Papacy?

Jesus certainly did not plan for the inflated and corrupt popes of the popular imagination. He intended to found a church, but the church was not democratic in structure. It was established with clear individual leadership. In Matthew 16.18-19 Jesus says to Simon Peter, “You are Peter, and on this Rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hell will not overcome it.” So, Jesus established his church not on a congregational model, but on the model of personal leadership.

Was this a monarchical papacy? In a way it was. In Matthew 16 Jesus goes on to say to Peter, “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” This is a direct reference back to Isaiah 22.22, where the prophet recognizes Eliakim as the steward of the royal House of David. The steward was the Prime Minister of the Kingdom. The keys of the kingdom were the sign of his personal authority delegated by the king himself.

Jesus never intended a monarchical papacy in the corrupt sense of the Pope being an absolute worldly monarch, but the church leadership Jesus intended was ‘monarchical’ in the sense that it was based on his authority as King of Kings.

The reference to Isaiah 22 shows that the structure of Jesus’ kingdom was modeled on King David’s dynastic court. In Luke 1.32-33 Jesus’ birth is announced in royal terms. He will inherit the throne of his father David. He will rule over the house of Jacob and his kingdom shall never end. Like Eliakim, to whom Jesus refers, Peter is to be the appointed authority in this court, and as such his role is that of steward and ruler in the absence of the High King, the scion of the House of David. That Peter assumes this pre-eminent role of leadership in the early church is attested to throughout the New Testament from his first place in the list of the apostles, to his dynamic preaching on the day of Pentecost, his decision making at the Council of Jerusalem and the deference shown to him by St Paul and the other apostles.

Did Jesus plan the monarchical papacy? He did not plan for the sometimes corrupt, venal and worldly papacy that it has sometimes become down through history, but Jesus did plan for one man to be his royal delegate on earth. He did plan for one man to lead the others (Lk.22.32) He did plan for one man to take up the spiritual and temporal leadership of his church. This is shown not only through the famous passage from Matthew 16, but also in the final chapter of John’s gospel where Jesus the Good Shepherd hands his pastoral role over to Peter.

Was the early church de-centralized?

Independent Evangelical churches follow the Baptist Successionist idea that the early church was de-centralized. They like to imagine that the early Christians met in their homes for Bible study and prayer, and that in this pure form they existed independently of any central authority. It is easy to imagine that long ago in the ancient world transportation and communication was rare and difficult and that no form of centralized church authority could have existed even if it was desirable.

The most straightforward reading of the Acts of the Apostles shows this to be untrue, and a further reading of early church documents shows this to be no more than a back-projected invention. In the Acts of the Apostles what we find is a church that is immediately centralized in Jerusalem. When Peter has his disturbing vision in which God directs him to admit the Gentiles to the Church, he references back at once to the apostolic leadership in Jerusalem.(Acts 11:2)

The mission of the infant church was directed from Jerusalem, with Barnabas and Agabus being sent to Antioch (Acts 11:22,27) The Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15) was convened to decide on the Gentile decision and a letter of instruction was sent to the new churches in Antioch, Syria and Cilicia. (Acts 15:23) We see Philip, John Mark, Barnabas and Paul traveling to and from Jerusalem and providing a teaching and disciplinary link from the new churches back to the centralized church in Jerusalem.

After the martyrdom of James the leadership shifts to Peter and Paul. The authority is not centered on Jerusalem, but through their epistles to the various churches, we see a centralized authority that is vested in Peter and Paul as apostles. This central authority was very soon focussed on Rome, so that St Ignatius, a bishop of the church in Antioch would write to the Romans in the year 108 affirming that their church was the one that had the “superior place in love among the churches.’”

Historian Eamon Duffy suggests that the earliest leadership in the Roman church may have been more conciliar than monarchical because in his letter to the Corinthians, Clement of Rome doesn’t write as the Bishop of Rome, but even if this is so Duffy confirms that the early church believed Clement was the fourth Bishop of Rome and read Clement’s letter as support for centralized Roman authority. He also concedes that by the time of Irenaeus in the mid second century the centralizing role of the Bishop of Rome was already well established. From then on, citation after citation from the apostolic Fathers can be compiled to show that the whole church from Gaul to North Africa and from Syria to Spain affirm the primacy of the Bishop of Rome as the successor of Peter and Paul.

The acceptance of this centralized authority was a sign of belonging to the one true church so that St Jerome could write to Pope Damasus in the mid 300s, “I think it is my duty to consult the chair of Peter, and to turn to a church whose faith has been praised by Paul… My words are spoken to the successor of the fisherman, to the disciple of the cross. As I follow no leader save Christ, so I communicate with none but your blessedness, that is with the chair of Peter. For this, I know, is the rock on which the church is built!”

Was the Early Church Local and Congregational?

We find no evidence of a network of independent, local churches ruled democratically by individual congregations. Instead, from the beginning we find the churches ruled by elders (bishops) So in the New Testament we find the apostles appointing elders in the churches. (Acts 14:23; Titus 1:5) The elders kept in touch with the apostles and with the elders of the other churches through travel and communication by epistle. (I Pt.1:1; 5:1) Anne Rice, the author of the Christ the Lord series of novels, points out how excellent and rapid the lines of communication and travel were in the Roman Empire.

In the early church we do not find independent congregations meeting on their own and determining their own affairs by reading the Bible. We have to remember that in the first two centuries there was no Bible as such for the canon of the New Testament had not yet been decided. Instead, from the earliest time we find churches ruled by the bishops and clergy whose authenticity is validated by their succession from the apostles. So Clement of Rome writes, “Our apostles also knew, through our Lord Jesus Christ, that there would be strife on the question of the bishop’s office. Therefore for this reason… they appointed the aforesaid persons and later made further provision that if they should fall asleep other tested men should succeed to their ministry.” Ignatius of Antioch in Syria writes letters to six different churches and instructs the Romans, “be submissive to the bishop and to one another as Jesus Christ was to the Father and the Apostles to Christ…that there may be unity.”

This apostolic ministry was present in each city, but centralized in Rome. The idea of a church being independent, local and congregational is rejected. Thus, by the late second century Irenaeus writes, “Those who wish to see the truth can observe in every church the tradition of the Apostles made manifest in the whole world…therefore we refute those who hold unauthorized assemblies…by pointing to the greatest and oldest church, a church known to all men, which was founded and established at Rome by the most renowned Apostles Peter and Paul…for this Church has the position of leadership and authority, and therefore every church, that is, the faithful everywhere must needs agree with the church at Rome for in her the apostolic tradition has ever been preserved by the faithful from all parts of the world.”

Did the Church only become hierarchical after Constantine?

Independent Evangelicals imagine that the church only became hierarchical after it was ‘infected’ by the emperor Constantine’s conversion in 315. At that time, they argue, the monarchical model came across from the court of the emperor and the church moved from being independent, local and congregational to being a centralized, hierarchical arm of the Roman Empire.

Again, this theory has no relation to reality.

As we have seen, the idea of a monarchical papacy was there from the beginning in Jesus’ identity as the Great scion of David the King with Peter as his steward. The steward, like the king he served, was to be the servant and shepherd of all, but he was also meant to rule as through the charism of individual leadership. This form of governance was hierarchical from the beginning for it is grounded in Jesus’ own concept of the Kingdom of God. A kingdom is hierarchical through and through, and the church, as Christ’s kingdom is hierarchical from its foundations. Furthermore, the leadership of the Jewish church (on which the Christian church was modeled) was hierarchical with it’s orders of rabbis, priests and elders.

Obedience to the bishop as the head of the church was crucial. So Ignatius of Antioch writes to the Christians at Smyrna and condemns individualistic congregationalism in terms that are clearly hierarchical: “All of you follow the bishop as Jesus Christ followed the Father, and the presbytery as the Apostles; respect the deacons as ordained by God. Let no one do anything that pertains to the church apart from the bishop. Let that be considered a valid Eucharist which is under the bishop or one who he has delegated….it is not permitted to baptize or hold a love feast independently of the bishop.”

The hierarchical nature of the church is confirmed and sealed through the apostolic succession. Church leaders are appointed by the successors of the apostles, and there is a clear chain of command which validates a church and it’s ministry. So Ireneaeus writes, “It is our duty to obey those presbyters who are in the Church who have their succession from the Apostles..the others who stand apart from the primitive succession and assemble in any place whatever we ought to regard with suspicion either as heretics and unsound in doctrine or as schismatics…all have fallen away from the truth.”

Throughout the New Testament and the writings of the Apostolic Fathers the church is portrayed as centralized, hierarchical and universal. The need for unity is stressed. Heresy and schism are anathema. Unity is guaranteed by allegiance to the clear hierarchical chain of command: God sent his Son Jesus. Jesus sent the Apostles. The Apostles appointed their successors. The Bishops are in charge. So Clement of Rome writes, “The Apostles received the gospel for us from the Lord Jesus Christ: Jesus the Christ was sent from God. Thus Christ is from God, the Apostles from Christ. in both cases the process was orderly and derived from the will of God.”

Was Leo the Great the First Pope?

The term ‘pope’ is from the Greek word ‘pappas’ which means ‘Father.’ In the first three centuries it was used of any bishop, and eventually the term was used for the Bishop of Alexandria, and finally by the sixth century it was used exclusively for the Bishop of Rome. Therefore it is an open question who was the first ‘pope’ as such.

The critics of the Catholic Church aren’t really worried about when the term ‘pope’ was first used. What they mean when they say that Leo the Great (440-461) was the first pope is that this is when the papacy began to assume worldly power. This is, therefore, simply a problem in definition of terms. By ‘pope’ the Evangelical means what I thought of as ‘pope’ after my Evangelical childhood. By ‘pope’ they mean ‘corrupt earthly ruler’. In that respect Leo the Great might be termed the ‘first pope’ because he was the one, (in the face of the disintegrating Roman Empire) who stepped up and got involved in temporal power without apology.

However, seeing the pope as merely a temporal ruler and disapproving is to be too simplistic. Catholics understand the pope’s power to be spiritual. While certain popes did assume temporal power, they often did so reluctantly, and did not always wield that power in a corrupt way. Whether popes should have assumed worldly wealth and power is arguable, but at the heart of their ministry, like the Lord they served, they should have known that their kingdom was not of this world. Their rule was to be hierarchical and monarchical in the sense that they were serving the King of Kings and Lord of Lords. It was not first and foremost to be hierarchical and monarchical in the worldly sense.

The Protestant idea that the papacy was a fifth century invention relies on a false understanding of the papacy itself. After the establishment of the church at Constantine’s conversion the church hierarchy did indeed become more influential in the kingdoms of this world, but that is not the essence of the papacy. The essence of the papacy lies in Jesus’ ordination of Peter as his royal steward, and his commission to assume the role of Good Shepherd in Christ’s absence. The idea, therefore, that Leo the Great was the first ‘pope’ is a red herring based on a misunderstanding of the pope’s true role.

The Early Church Today

From the Reformation onward, Protestant Christians have fallen into the trap of Restorationism. This is the idea that the existing church has become corrupt and departed from the true gospel and that a new church that is faithful to the New Testament can be created. These sincere Christians then attempt to ‘restore’ the church by creating a new church. The problem is, each new group of restorationists invariably create a church of their own liking determined by their contemporary cultural assumptions. They then imagine that the early church was like the one they have invented.

All of the historical documents show that, in essence, the closest thing we have today to the early church is actually the Catholic Church. In these main points the Catholic Church is today what she has always been. Her leadership is unapologetically monarchical and hierarchical. Her teaching authority is centralized and universal, and the pope is what he has always been, the universal pastor of Christ’s Church, the steward of Christ’s kingdom and the Rock on which Christ builds his Church.

If you like what you read here please consider becoming a Donor Subscriber. Donor Subscribers help keep the blog free of all advertising, help with the hosting and design costs and in thanks they receive special benefits, extra content and free offers. Go here to learn more.

This article was first published in This Rock magazine.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.