Every good fantasy story needs a magician. Dorothy encounters the Wizard of Oz. Frodo travels with Gandalf, Harry Potter has his Dumbledore and Arthur his Merlin.

A magus is a wise man, a shaman or a master of the ancient lore. The word “magician” comes from the Persian “magus” the name of the venerable sect of occult, astrologically adept wizards who were Nebuchadnezzar’s necromancers and Cyrus’ stargazers.

Indeed, the magician mentor is a staple character in every hero’s quest. The wise old man or woman offers guidance and supernatural insight. Like the oracles or Tiresias, he or she is a seer and a soothsayer.

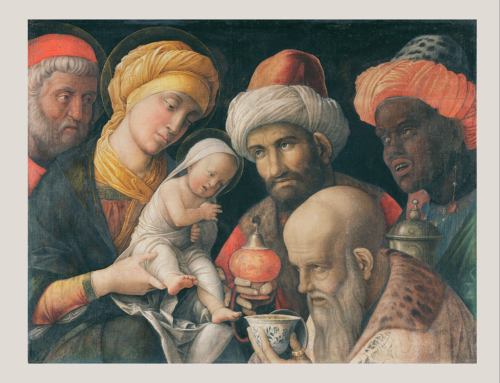

It is easy to understand, therefore, why skeptical New Testament scholars have relegated the magi from Matthew’s gospel to the realm of fantasy. Most ordinary Christians send their Christmas cards and attend church, never knowing that the majority of Bible scholars don’t believe the wise men existed at all. Furthermore, these scholars have taught most of the clergy that the wise men are fiction not fact. For all their lack of historical reality the three wise men might as well be named Gandalf, Merlin and Dumbledore rather than Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar.

The scholars’ conclusions rests on their modernists’ anti-supernatural bias. For them the story of the Magi’s visit to Bethlehem simply has too many supernatural aspects to be historically true.

The rationalist says it all sounds too much like a fairy tale. A magical star that guides the wise men to the birthplace of the infant king? We know stars don’t move like that. It’s too much like Jiminy Cricket singing, “When You Wish Upon a Star.”

A wicked king who wants to kill the baby prince in a fit of jealous rage? It sounds like the Queen who wants to kill Snow White with a poison apple. An pretty angel who appears and tells the wise men to go home a different way? I’m thinking kindly fairy godmothers who materialize to help the hero with the wave of a wand.

The modernists’ conclusions have been bolstered by two thousand years of the magi tradition being elaborated like no other gospel story. Influenced by Zoroastrianism and the Kaballah, the Gnostics in the second and third century picked up Matthew’s story of the magi and ran with it. With their fascination for fantasy stories, far out theories and fantastical theologies, the idea that mystical magicians from the mysterious land of Persia visited the Christ child was too magically, marvelous to resist.

For example, the third century Legend of Aphroditianus is an apocryphal gnostic text that begins with the account of a miracle in the temple of a pagan goddess in Persia at the time of Christ’s birth. According to the myth, the statues in the temple dance and sing and announce that the goddess Hera has been made pregnant by Zeus.

Suddenly a star appears above the statue of the goddess Hera. A voice from heaven is heard and all the dancing statues fall on their faces. The wise men of the court take this to mean that a King is to be born in Judah. That evening the god Dionysus confirms their interpretation. Then the king sends the Magi to Judea with gifts, the star pointing them along their way. The story tells of the Magi’s journey to Bethlehem, and how they meet the Jewish leaders and finally Mary and Jesus. They return to Persia bringing a portrait of Jesus and Mary and put it in the temple where the star first appeared.

Another ludicrous apocryphal text is The Revelation of the Magi. This story from the fifth century, pretends to be told by the magi themselves. The wise men are residents of a mythical land called Shir in the Far East. They are the descendants of Seth, the third son of Adam and Eve, who passed on to them a prophecy from his father that one day a star of amazing brightness would appear to announce the birth of God in human form.

The story continues as every year the mystical magi of Shir ascended their Holy Mountain where the Cave of Treasures is located. This cave contains the wisdom of Seth and the treasures of Adam and it is there that the super bright star—brighter than the sun appears to them as a tiny, radiant human. The star child tells them to go on a long journey to Bethlehem. After long preparations they set off only to find that the star child accompanies them removing all obstacles and miraculously providing them with food and protection.

Once they get to Bethlehem, Mary accuses them of wanting to steal the child, but they inform her that he is the savior of the world. Finally they go home provided with more miraculous food.

Alas, these ridiculous tales became part of the mixed bag of traditions about the Biblical magi. As the stories developed it became accepted truth that the magi were kings, that they rode camels, that there were three of them, that they came from India, Arabia and Africa and that they were named Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar. Over the centuries the stories became increasingly elaborate and ornate as the gold and enameled reliquary that supposedly houses their relics in Cologne Cathedral.

Matthew’s simple story of the Magi therefore became encrusted with the most marvelous, (but fictitious) traditions. It all makes for a lovely Christmas, but it has been difficult for the experts to see past all the accretions and ask whether there might, after all, be some historical basis in the magi story. To do so is professional suicide.

For a serious New Testament scholar to suggest that there is a historical basis for the magi story is akin to a geologist proposing that God might have created the world on October 23, 4004 BC. As one Biblical professor confessed to me, “If you want a career in New Testament scholarship, the historicity of the magi story is a no go area.”

Happily I have no pretensions to a career in New Testament scholarship. Therefore, for my latest book I have plunged into the question of whether there might be a historical foundation for the magi story. The answers I have discovered are fascinating and exciting. New technologies, new textual finds and fresh archeological discoveries have unlocked some secrets which reveal for the first time the historicity and the true identity of the wise men.

The magi were not fanciful magical figures from the imagination of Matthew. Instead there is every reason to believe they were historical figures who fit perfectly into the political, religious and cultural scene in Judea at the time of Christ’ birth. The Magi were wise counsellors to the court of the Nabatean king Aretas IV. On discerning the birth of a new heir to the Judean throne, they had every motivation to pay a diplomatic visit to their neighbor Herod the Great.

As I uncovered the astounding details in this quest I became as excited by what I have discovered as Indiana Jones might have been at finding Merlin’s tomb.

Go here for more information on The Mystery of the Magi-The Quest to Identify the Three Wise Men.

Father Longenecker,

If you haven’t seen the Star of Bethlehem documentary, I highly recommend watching it. It’s been on EWTN in year’s past. There is also a website.

The first time I saw it I cried. I love the motion of the planets and the stars. It very much so had personal meaning for me.

Can’t wait to watch it again.

God bless.

I have seen it. It comprised part of my research for my book on the Magi