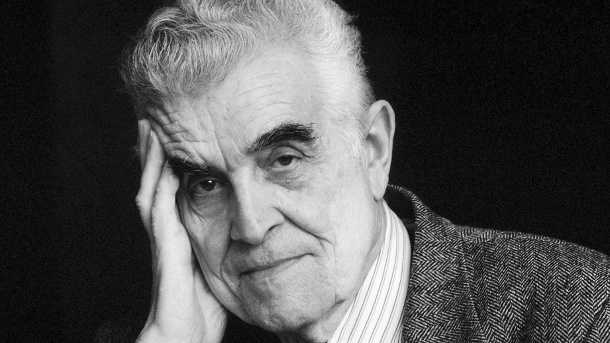

I’ve been re-reading some stuff by Rene Girard (pictured here) and books about his thought. For those of you who are unfamiliar, Girard was a literary critic and anthropologist. The germ of his thought can be summarized thus:

Girard’s fundamental ideas, which he had developed throughout his career and provided the foundation for his thinking, were that desire is mimetic (i.e. all of our desires are borrowed from other people), that all conflict originates in mimetic desire (mimetic rivalry), that the scapegoat mechanism is the origin of sacrifice and the foundation of human culture, and religion was necessary in human evolution to control the violence that can come from mimetic rivalry, and that the Bible reveals these ideas and denounces the scapegoat mechanism.

The part that interests me most is the theology and Biblical connections. Girard believes that the scapegoat mechanism–blaming others–and projecting one’s evil on to them–is broken from the inside out the the death of Christ on the cross. For the first time human beings began to view the violence as wrong and view the victim with compassion and pity.

This creates, for the first time in human history, a narrative of compassion for the poor, the outsider, the victim, the refugee, the homeless etc.

What I have not found in the secondary literature are two strands that come from this. Firstly, the relevance and importance of the liturgy of the Mass. In primitive societies (according to Girard) the corporate tendency to violence is sacralized or made acceptable through the ritual of sacrifice–at first human sacrifice and then animal substitutes. At the cross of Christ the sacrificial system was ended once and for all. Christ broke it from the inside out.

However, we still celebrate the “sacrifice of the Mass”. Why? The Catholic teaching is that we “re-present” the once for all sacrifice of Christ on the cross, and we thereby remember and participate in that action through the action of the Mass. We offer the sacrifice of the Mass not to offer a fresh sacrifice to God but to remember and give thanks for the one sacrifice that abolished that sacrificial system. I am not done reading the secondary literature nor all of Girard, but I have not found anyone yet who has made the connection that it is through the continual offering of the Mass that a society has the same outlet for corporate violence–not through a real sacrifice, but through a memory of the sacrifice that takes the place of a sacrificial system.

The second aspect is the practicality of Christianity in dealing with the violence in society. Violence in society is rooted in envy. “I want what you have and if you won’t give it to me I am going to take it.” How does Christianity cope with this urge? Not so much through law enforcement, but through charity. The Christian church, from the beginning began to respond to the compassion for the victim by helping the victim. It was Christians who began to change the world by starting orphanages, building hospitals and schools and homes for the poor. It was Christians who began the work of social justice and campaigned for the poor, the marginalized, the hungry and the orphans and prisoners.

These two things together turn the world upside down. These two actions together (if you like) loving God and loving our neighbor–are the things which turn the tide of violence and should change humanity and change the world.

The only other option is an endless cycle of envy, violence and revenge.

[…] Ph. Lawler A Very Bad Argument for Priestly Celibacy – Bishop Robert Barron, Word on Fire Rene Girard, Sacred Violence & the Mass – Fr. Dwight Longenecker Czech Brutalism – Rod Dreher, TAC Blogger Chemical Weapons Are […]